Dupilumab in Dermatology: Mechanism, Benefits, and Considerations

Introduction

Dupilumab (Dupixent®) is a monoclonal antibody therapy designed to treat inflammatory conditions, primarily atopic dermatitis. It is the first biologic treatment approved for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis and has since been expanded to other allergic and inflammatory diseases. By blocking specific immune signaling pathways, dupilumab offers an effective alternative for patients who do not respond adequately to conventional therapies.

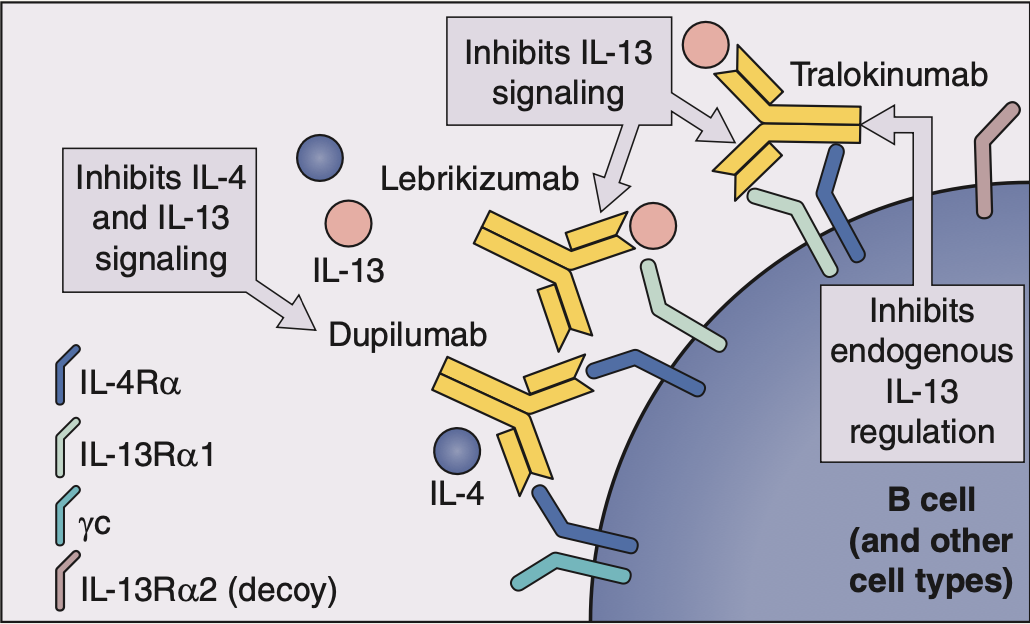

Mechanism of Action

Dupilumab is a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to the IL-4Rα subunit, a key component of the receptor shared by interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-13 (IL-13). These two cytokines play a crucial role in Th2-mediated inflammation, which is a major driver of conditions like atopic dermatitis and asthma. By inhibiting IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, dupilumab reduces inflammation, improves skin barrier function, and alleviates symptoms.

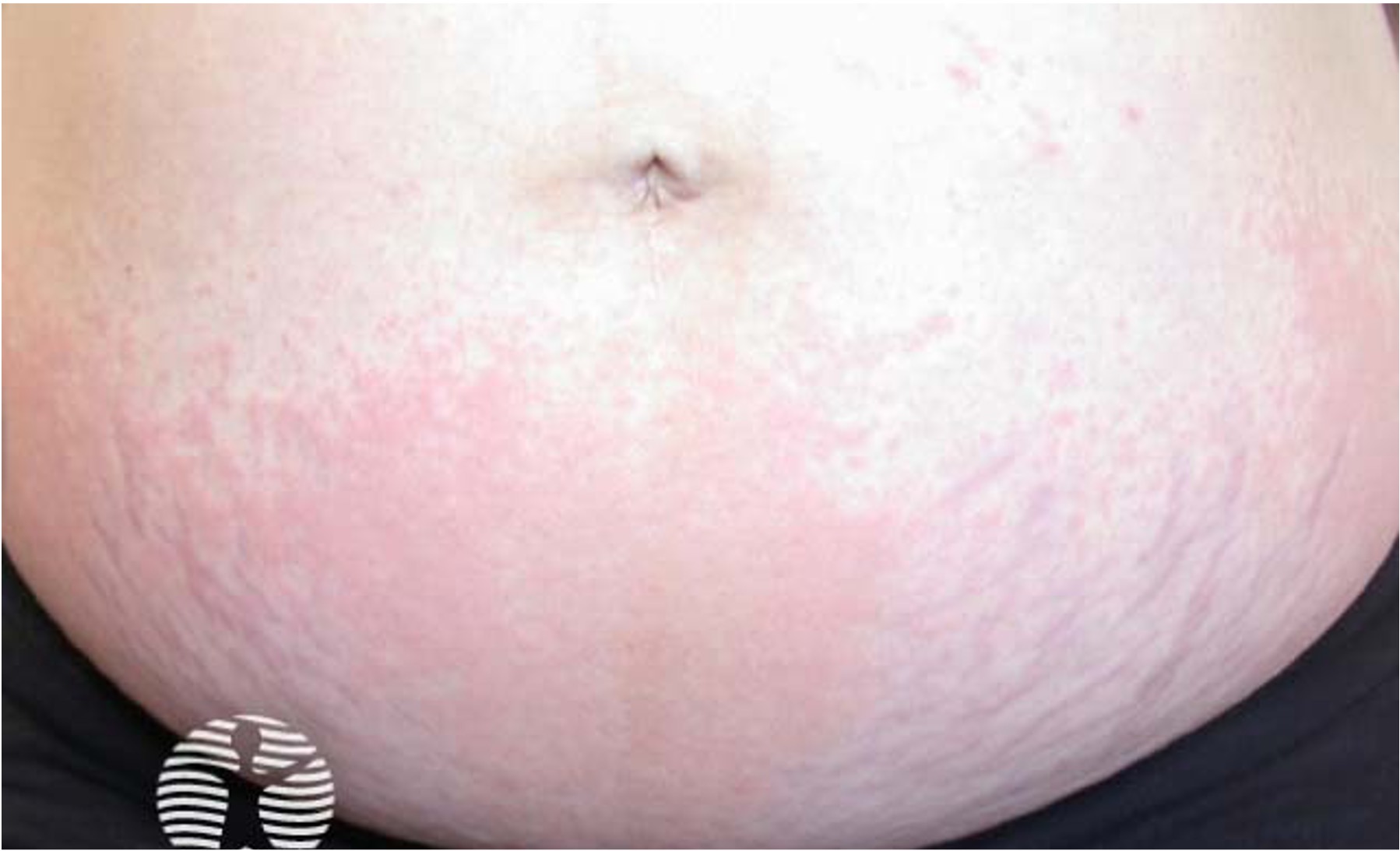

Indications

Dupilumab is FDA-approved for the treatment of:

- Atopic dermatitis (eczema) in patients ≥6 months old with moderate-to-severe disease that is inadequately controlled with topical treatments.

- Prurigo nodularis in adults.

- Asthma in patients ≥6 years old with moderate-to-severe disease.

- Eosinophilic esophagitis in patients ≥12 years old.

- Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in adults.

Additionally, off-label uses of dupilumab are being explored for spontaneous chronic urticaria, nummular eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, chronic hand eczema, bullous pemphigoid, and Netherton syndrome.

Dosage and Administration

Dupilumab is administered via subcutaneous injection, with dosing dependent on age and weight:

- Adults and children (≥60 kg): 600 mg loading dose, then 300 mg every 2 weeks.

- Children (30–59 kg): 400 mg loading dose, then 200 mg every 2 weeks.

- Children (15–29 kg, ≥6 years old): 600 mg loading dose, then 300 mg every 4 weeks.

- Children (5–14 kg, ≤5 years old): 200 mg every 4 weeks.

Contraindications and Precautions

Dupilumab is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or its components. Additionally, live vaccines should be avoided, and patients should be up to date on their vaccinations before starting therapy.

Patients with serious active helminth infections (parasitic worms) should be treated before starting dupilumab.

Adverse Effects

While generally well-tolerated, dupilumab can cause certain side effects, the most common being:

- Injection site reactions

- Ocular diseases (conjunctivitis, dry eyes, blepharitis, keratitis)

- Herpes infections

- Atopic dermatitis exacerbation

- Nasopharyngitis (common cold symptoms)

- Headache and upper respiratory infections

Ocular side effects occur in approximately 10% of patients and usually develop within the first few weeks to months of treatment. Artificial tears, antihistamine eye drops (e.g., ketotifen), corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and tacrolimus ointment may be used for management.

Some patients may also experience facial or neck erythema, or dermatitis that is possibly linked to rosacea, allergic contact dermatitis, or Malassezia related dermatitis.

Rare but reported conditions associated with dupilumab include psoriasiform eruptions, lichen planus-like reactions, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Clinical Outcomes and Efficacy

Clinical trials have demonstrated that 40–50% of adolescents and adults receiving dupilumab alone, and 60–70% of children or adults receiving it in combination with topical corticosteroids, achieve a 75% improvement in their Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75).

Conclusion

Dupilumab has revolutionized the management of atopic dermatitis and other Th2-driven inflammatory conditions, offering a safe and effective option for patients with moderate-to-severe disease. While its side effects, particularly ocular symptoms, should be monitored, its benefits in reducing inflammation and improving quality of life make it a cornerstone therapy in dermatology and beyond.

Written by:

Naif Alshehri, Medical Intern

Resources:

Saudi MOH Atopic Dermatitis Guidelines

Dermnet

Bolognia Dermatology Textbook 5th Edition

Muñoz-Bellido FJ, Moreno E, Dávila I. Dupilumab: A Review of Present Indications and Off-Label Uses. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2022;32(2):97-115. doi:10.18176/jiaci.0682

Second Picture Resource:

Bolognia Dermatology Textbook 5th Edition