Fox-Fordyce Disease: The Sweat Retention Disease

Fox-Fordyce disease, also called apocrine miliaria, is a chronic rare condition where the apocrine sweat is retained and causes inflammation. Post-pubertal women between the ages of 13 and 35 are most commonly affected. Males and children can sometimes be affected.

Etiology and pathophysiology:

There is no known cause of Fox-Fordyce disease. In the hair follicle, a keratotic block traps apocrine perspiration. The epidermis’s apocrine sweat ducts burst and leak, resulting in swelling and agonizing itching. There are several factors recognized for the development of this disease including alteration of sweat components, emotional and hormonal influences, and laser hair removal. Heat, humidity, friction, and stress are common environmental factors that contribute to the disorder.

Clinical features:

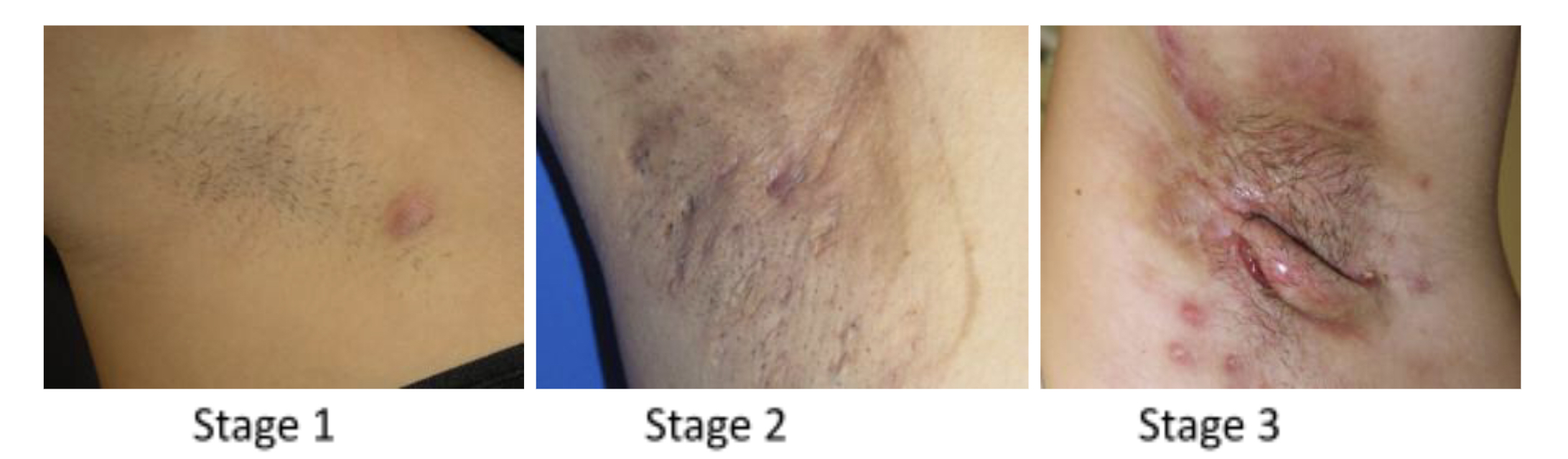

Apocrine sweat glands are exclusively located in the axilla, pubic region, and around the nipples, hence Fox-Fordyce disease is distinguished by itching lumps around the hair follicles in these places. The following clinical findings are often found with this disease includes bilateral dome-shaped flesh-coloured to small reddish papules affecting hair follicles, secondary skin lesion due to starching (lichenification), and reduced or absent sweating in the affected region. Loss of hair in the affected area is frequently observed.

Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of Fox-Fordyce disease is typically made clinically; dermoscopy features include central hyperkeratotic plug in each papule, multiple light brown to dark structureless areas, lack of pigment network, and folliculocentric papule.

Skin biopsy results show keratotic plug, spongiosis and vesicle formation, perifollicular infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells, and xanthomatous foamy cells.

Management:

There is no definitive cure for this disease. One of the first treatments used is frequently topical and intralesional corticosteroids. Topical calcineurin inhibitors might lessen itching and make skin lesions look better. Topical tretinoin has been demonstrated to lessen pruritus but has little impact on how the condition manifests clinically and may irritate. Clindamycin lotion applied twice daily could also help to lessen symptoms. While some individuals have short relief from oral isotretinoin, some women respond to oral contraceptives. Phototherapy, electrocautery, and periareolar skin excision are examples of physical therapies that could be helpful.

Prognosis:

Fox-Fordyce disease could linger for a long time. It may occasionally go away during pregnancy. Others may experience a menopausal resolution or a continuing problem.

Written by:

Mohammed Alahmadi, medical Student.

Revised by:

Maee Barakeh, medical student.

References:

DermNet

Bolognia Textbook of Dermatology

Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology