Psoriasis is being treated with a variety of medicines that are currently being researched. These treatments are intended to treat psoriasis through a number of methods, including:

Therapies targeting the Th17 pathway – Interleukins (ILs) from the T helper type 17 (Th17) pathway (IL-23 and IL-17) play a key role in psoriasis pathogenesis and have become therapeutic targets:

Bimekizumab – Bimekizumab, a monoclonal IgG1 antibody that suppresses IL-17A and IL-17F, has been shown to be effective in phase III randomized studies. Adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis were randomly randomized to receive bimekizumab (320 mg every four weeks) or placebo in a 4:1 ratio in the BE READY study (n = 435). At week 16, 317 of 349 bimekizumab patients (91%) had a 90 percent improvement in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 90), compared to only 1 of 86 patients (1%) in the placebo group. Over the next 40 weeks, patients in the bimekizumab group who attained PASI 90 were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive bimekizumab 320 mg every four weeks, bimekizumab 320 mg every eight weeks, or placebo. Patients who received bimekizumab every four or eight weeks were more likely than those in the placebo group to reach PASI 90 at week 56. (87, 91, and 16 percent, respectively). Nasopharyngitis, oral candidiasis, and upper respiratory tract infections were the most prevalent treatment-emergent adverse events for bimekizumab.

Bimekizumab, ustekinumab, and placebo were tested in the BE VIVID study (n = 567) for effectiveness and safety. For 16 weeks, adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis were given bimekizumab (320 mg every four weeks), ustekinumab (weight-based dosage of 45 or 90 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks), or placebo (every four weeks). Patients in the placebo group switched to bimekizumab at week 16, while those in the active treatment groups stayed on it until week 52. Patients in the bimekizumab (n = 321) group were more likely than those in the ustekinumab (n = 163) and placebo (n = 83) groups to attain PASI 90 at week 16. (PASI 90 achieved in 85, 50, and 5 percent of patients, respectively). Nasopharyngitis, oral candidiasis, and upper respiratory tract infection were the most prevalent treatment-emergent adverse events for bimekizumab, with candidiasis occurring more often in the bimekizumab group than in the ustekinumab group. Over the course of 52 weeks, five serious cardiac adverse events occurred in bimekizumab-treated individuals with pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors, but none happened in the ustekinumab-treated group.Oral candidiasis was more common than with other IL-17 pathway inhibitors, and one instance of inflammatory bowel illness was reported. Additional research might help to clarify the issue of safety.

Trials comparing bimekizumab to adalimumab or secukinumab show that bimekizumab is more effective. Adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis were randomly allocated to bimekizumab (320 mg every four weeks for 56 weeks), bimekizumab (320 mg every four weeks for 16 weeks and then every eight weeks until week 56), or adalimumab in a 56-week phase III study (BE SURE trial) (80 mg followed by 40 mg one week later and then 40 mg every two weeks until week 24).

Patients who received adalimumab were then given bimekizumab (320 mg every four weeks from week 24 to 56). At week 16, 275 of 319 patients (86%) who received bimekizumab had a PASI of 90, compared to 75 of 159 patients (47%) who received adalimumab (adjusted risk difference 28.2 percentage points, 95 percent CI 19.7-36.7). With both bimekizumab dose regimens, responses were sustained until week 56.

Adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis were randomly allocated to bimekizumab (320 mg every four weeks) or secukinumab in a 48-week phase III study (BE RADIANT trial) (300 mg weekly to week 4 and then once every four weeks). Bimekizumab patients were rerandomized at week 16 to receive bimekizumab once every four weeks or once every eight weeks. At week 16, 230 of 373 bimekizumab patients (62%) had complete eradication of skin disease on the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 100), compared to 181 of 370 patients (49%) in the secukinumab group (adjusted risk difference 12.7 percentage points, 95 percent CI 5.8-19.6). Bimekizumab’s effectiveness remained better after 48 weeks (PASI 100 in 67 versus 46 percent of patients). The study’s power to identify differences between the two bimekizumab maintenance therapy groups was insufficient.

Tapinarof – Tapinarof is a topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modifying drug that may help with psoriasis by modulating Th17 cytokines including IL-17A and IL-17F, as well as normalizing the skin barrier and providing antioxidant action. A total of 1025 persons with chronic plaque psoriasis encompassing 3 to 20% of total body surface area were randomly allocated in a 2:1 ratio to either tapinarof 1 percent cream or vehicle used once daily in two similar phase III studies (PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2). Patients in the tapinarof groups were more likely than patients in the placebo group to achieve the primary endpoint of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) and a two-point decrease in the five-point PGA scale at week 12. (35.4 versus 6 percent [adjusted difference 29.4 percentage points; relative rate 5.8, 95 percent CI 2.9-11.5] in PSOARING 1 and 40.2 versus 6.3 percent [adjusted difference 33.9 percentage points; relative rate 6.1, 95 percent CI 3.3-11.4] in PSOARING 2). The tapinarof groups improved 75% more than the vehicle groups in terms of the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) and PASI 90 rates. In the tapinarof groups, foliculitis, contact dermatitis, and headache were more common than in the other groups. In the tapinarof groups, folliculitis, contact dermatitis, and headache were more common than in the vehicle groups.

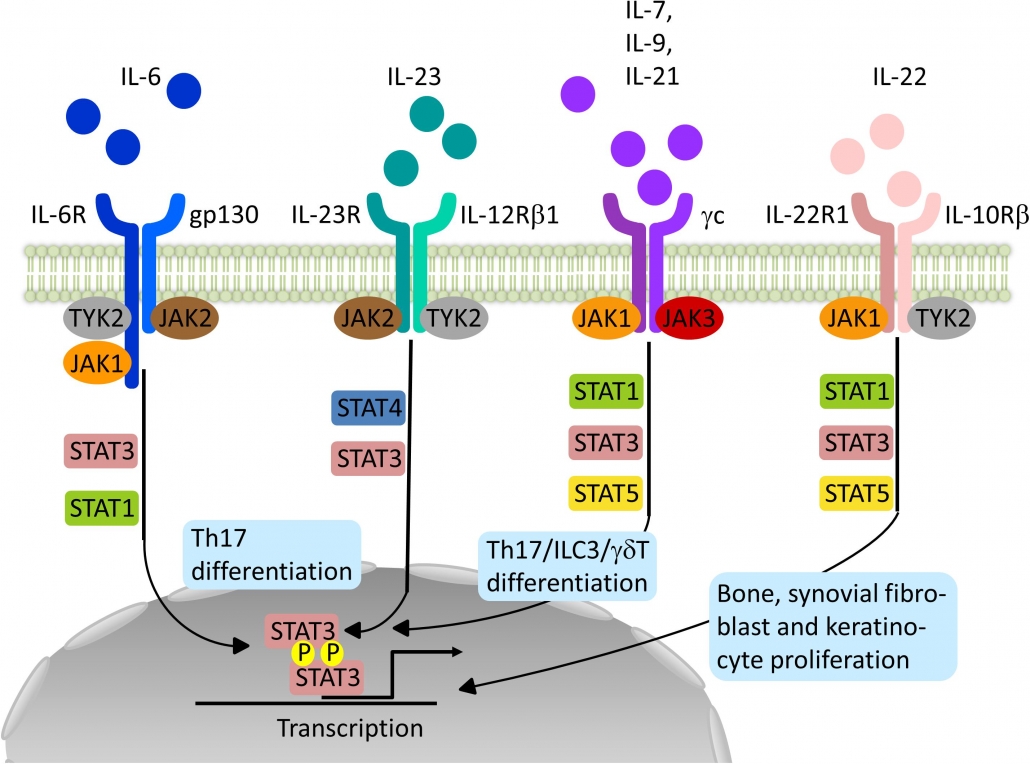

Small molecules – Other possible treatments include a variety of tiny compounds that aim to disrupt cellular signaling, which is crucial for the propagation of the inflammatory response. Small compounds that block Janus kinases (JAKs), lipids, a protein kinase C inhibitor, a selective tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor, and crisaborole, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor are some of the small molecules being researched for the treatment of psoriasis:

- In randomized studies, oral tofacitinib, a small molecule JAK inhibitor licensed for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis, was beneficial for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily was superior to placebo and noninferior to etanercept in a phase III trial that randomly assigned 1106 adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis to treatment with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily, tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, etanercept (50 mg twice weekly), or placebo.By week 12, 64, 40, 59, and 6% of patients receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily, tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, etanercept, and placebo, respectively, had met this objective. Other phase III studies found tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily and tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily to be helpful for chronic plaque psoriasis. The finest outcomes come from taking 10 mg twice a day. Tofacitinib has a quick beginning of action, with responses visible by week 4, and there is evidence of tofacitinib’s effectiveness for up to two years. In most cases, the treatment is well tolerated. Tofacitinib may make you more susceptible to infection. Cholesterol and creatine phosphokinase levels may also rise during treatment. A phase II randomized study also indicated that a topical formulation of tofacitinib was more efficacious than vehicle for plaque psoriasis.

- In a phase II, dose-ranging, randomized study, baricitinib, another oral reversible inhibitor of JAK1/JAK2 tyrosine kinases, was examined for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. 271 participants were randomly randomized to receive daily dosages of baricitinib 2, 4, 8, or 10 mg, or a placebo, in this trial. More patients in the baricitinib 8 and 10 mg groups attained PASI 75 at 12 weeks than those in the placebo group (43, 54, and 17 percent, respectively). Infections, lymphopenia, neutropenia, anemia, and an increase in creatine phosphokinase were more prevalent among patients receiving the highest baricitinib dosages.

- Selective inhibition of TYK2, an intracellular signaling enzyme implicated in psoriasis pathogenesis, using the experimental drug BMS-986165 was related with clinical improvement in people with moderate to severe psoriasis in a phase II study (n = 268) [237]. Participants were allocated to one of five BMS-986165 dosage regimens or a placebo. More patients receiving 3 mg daily, 3 mg twice daily, 6 mg twice daily, or 12 mg daily of BMS-986165 attained PASI 75 after 12 weeks than patients receiving placebo (39, 69, 67, 75, and 7 percent, respectively). A three-milligram dosage given every other day did not outperform the placebo. In the active therapy groups, adverse events were more prevalent. Nasopharyngitis, headache, diarrhea, nausea, and upper respiratory infection were the most prevalent side effects. Mild to severe acne was more common in the active treatment groups, and one melanoma diagnosis was made in the 3 mg daily group.

- Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1), a receptor involved in lymphocyte migration from secondary lymphoid tissues into the bloodstream, might be another viable treatment for psoriasis. Ponesimod, a selective S1PR1 modulator also being explored for the treatment of multiple sclerosis, causes S1PR1 internalization, preventing lymphocyte egress triggered by sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P). Individuals treated with ponesimod were considerably more likely than patients treated with placebo to attain PASI 75 after 16 weeks in a phase II randomized study including 326 patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis.

- Treatment with a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) analog (exenatide or liraglutide) seems to induce moderate improvement in psoriasis in people with both psoriasis and type 2 diabetes in small, uncontrolled studies. Liraglutide, on the other hand, was shown to be ineffective for plaque psoriasis in a placebo-controlled randomized study (n = 20).

- Treatment with topical crisaborole, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, has been linked to improvements in facial psoriasis, intertriginous psoriasis, and palmoplantar psoriasis, all of which manifest as erythematous plaques, papules, and deep-seated pustules on the palms and soles, according to case reports.

Topical calcineurin inhibitor – Treatment with topical crisaborole, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, has been linked to improvements in facial psoriasis, intertriginous psoriasis, and palmoplantar psoriasis, all of which manifest as erythematous plaques, papules, and deep-seated pustules on the palms and soles, according to case reports.

written by: Lama Altamimi, medical intern

references:

UPTODATE