Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (HFMD)

Background

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (HFMD) is a common, self-limiting viral infection primarily affecting children under five years old. Characterized by a distinctive rash and oral lesions, HFMD occurs worldwide, with increased incidence during late summer and early autumn.

Etiology

HFMD is predominantly caused by coxsackievirus A16 and enterovirus 71, both members of the Enterovirus genus. Transmission occurs through direct contact with nasal secretions, saliva, blister fluid, or stool of infected individuals. The virus can also spread via respiratory droplets or contaminated surfaces, making it highly contagious, especially in childcare settings.

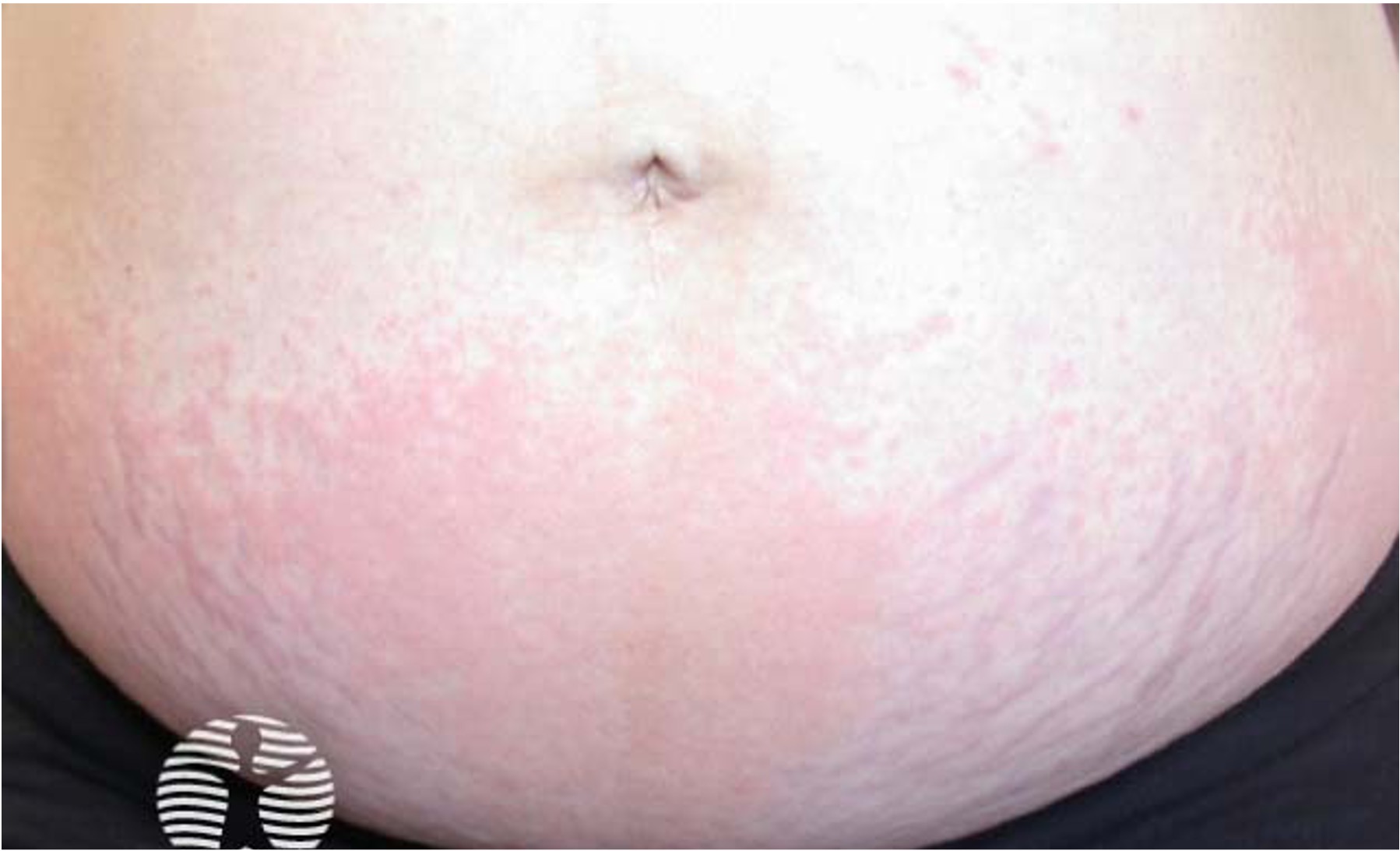

Clinical Features

After an incubation period of 3 to 5 days, initial symptoms include fever, malaise, and sore throat. Within a few days, painful oral lesions develop, appearing as red macules that progress to vesicles and ulcers, commonly located on the tongue, gums, and inside of the cheeks. Simultaneously or shortly after, a non-itchy rash emerges on the palms, soles, and sometimes the buttocks, presenting as red macules or vesicles. These skin lesions are typically not painful.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on the characteristic presentation of oral ulcers and a distinctive rash on the hands and feet. Laboratory tests are generally not required but may be used in atypical cases or when complications arise. The preferred confirmatory test is polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which can detect enteroviruses from throat swabs, stool samples, or vesicle fluid. Serologic tests and viral culture are rarely performed due to limited clinical utility and slow turnaround times.

Management

Treatment focuses on symptomatic relief, as HFMD is self-limiting and typically resolves within 7 to 10 days. Recommended measures include:

- Pain Relief: Administering acetaminophen or ibuprofen to alleviate fever and discomfort.

- Hydration: Encouraging fluid intake to prevent dehydration, especially in children with painful oral lesions.

- Topical Treatments: Using mouthwashes or sprays to reduce oral discomfort.

Antiviral medications are not indicated, and antibiotics are ineffective unless a secondary bacterial infection develops.

Prevention

Preventative strategies focus on limiting the spread of the virus:

- Hygiene Practices: Regular handwashing with soap and water, especially after diaper changes or using the toilet.

- Cleaning: Disinfecting contaminated surfaces and objects, such as toys and doorknobs.

- Isolation: Keeping infected individuals, particularly children, away from school or daycare during the acute phase of the illness to reduce transmission.

Currently, no vaccines are available for HFMD, making these preventive measures crucial.

Prognosis

HFMD generally has an excellent prognosis, with most individuals recovering fully without complications. However, rare severe manifestations can occur, especially with enterovirus 71 infections, including neurological complications like aseptic meningitis or encephalitis. Prompt medical attention is essential if neurological symptoms or signs of dehydration arise.

In conclusion, Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease is a common viral illness with distinctive clinical features. Understanding its etiology, clinical presentation, and management strategies is vital for effective care and prevention.

Written by:

Dr Renad AlKanaan

Revised by:

Naif Alshehri, Medical Intern

References:

Dermnet

UpToDate

Bolognia 5th Edition